| Ils sont nés un 8 septembre |

| Jean-Louis Barrault, Anton Dvorak, Alfred Jarry, Peter Sellers, Jean-Philippe Apathie. |

|

Sun enters the next Sabian symbol at 10:36 h (chart) |

Mercredi 8 septembre :

|

| |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sabian Symbol:

A vast display of cosmic forces is seen in the eruption of a volcano with dust clouds, flowing lava, earth rumblings.

Sabian Symbol:

A pilgrim sits on a rustic bench and one-by-one his ideals in a sort of trance vision take form before him.

Sabian Symbol:

A children's birthday party is in progress; on a side porch a group of youngsters are blowing soap bubbles.

Sabian Symbol:

A man stands alone in surrounding gloom; were his eyes open to spirit things he would see helping angels arriving.

Sabian Symbol:

A highly ritualistic service is in process; officiating priests are automatons, a boy with a censer is rapt-eyed.

Sabian Symbol:

A butterfly struggles to emerge from the chrysalis and it seems that the right wing is more perfectly formed.

Sabian Symbol:

The fall-fashion display has opened in the fine stores and in their windows are beautifully gowned wax figures.

Sabian Symbol:

A man in evening clothes, muffled to breast the storm through which he walks, yet wears his top hat rakishly.

Sabian Symbol:

Down the man-made mountain of industry in allegorical representation some the prophet with tablets of a new law.

Sabian Symbol:

The little boys are welcomes to the store of the genial oriental rug dealer for rare fun in piled softness.

Sabian Symbol:

A woman is great with child; the remarkable thing is that she was impregnated by her own spirit or aspiration.

Sabian Symbol:

The window of a farmhouse yields its view of soft purple fields and the table is set for a quiet supper.

Sabian Symbol:

In a curious allegorical transformation a flag becomes an eagle, and the eagle becomes chanticleer triumphant.

| Planet | Longitude | Daily Path | RA | Decl. | H | Str. | Fixed Stars | |

| 9 | ||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||

| 12 | ||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||

| 6 |

| Planet | Longitude |

| Sun | 16 Vir 06' 22" |

| Moon | 05 Lib 47' 53" |

| Mercury | 12 Lib 10' 53" |

| Venus | 27 Lib 20' 03" |

| Mars | 25 Vir 50' 09" |

| Jupiter | 24 Aqu 46' 56" R |

| Saturn | 07 Aqu 43' 31" R |

| Uranus | 14 Tau 38' 15" R |

| Neptune | 21 Pis 56' 47" R |

| Pluto | 24 Cap 29' 58" R |

| Chiron | 11 Ari 44' 20" R |

| Lilith | 05 Gem 46' 51" |

| True Node | 05 Gem 01' 52" R |

8-Sep-2021, 13:13 UT/GMT | ||||

| Sun | 16 | 6'22" | |

| Moon | 5 | 47'47" | |

| Mercury | 12 | 10'53" | |

| Venus | 27 | 20' 2" | |

| Mars | 25 | 50' 9" | |

| Jupiter | 24 | 46'56"r | |

| Saturn | 7 | 43'31"r | |

| Uranus | 14 | 38'15"r | |

| Neptune | 21 | 56'47"r | |

| Pluto | 24 | 29'58"r | |

| TrueNode | 5 | 1'52"r | |

| Chiron | 11 | 44'20"r | |

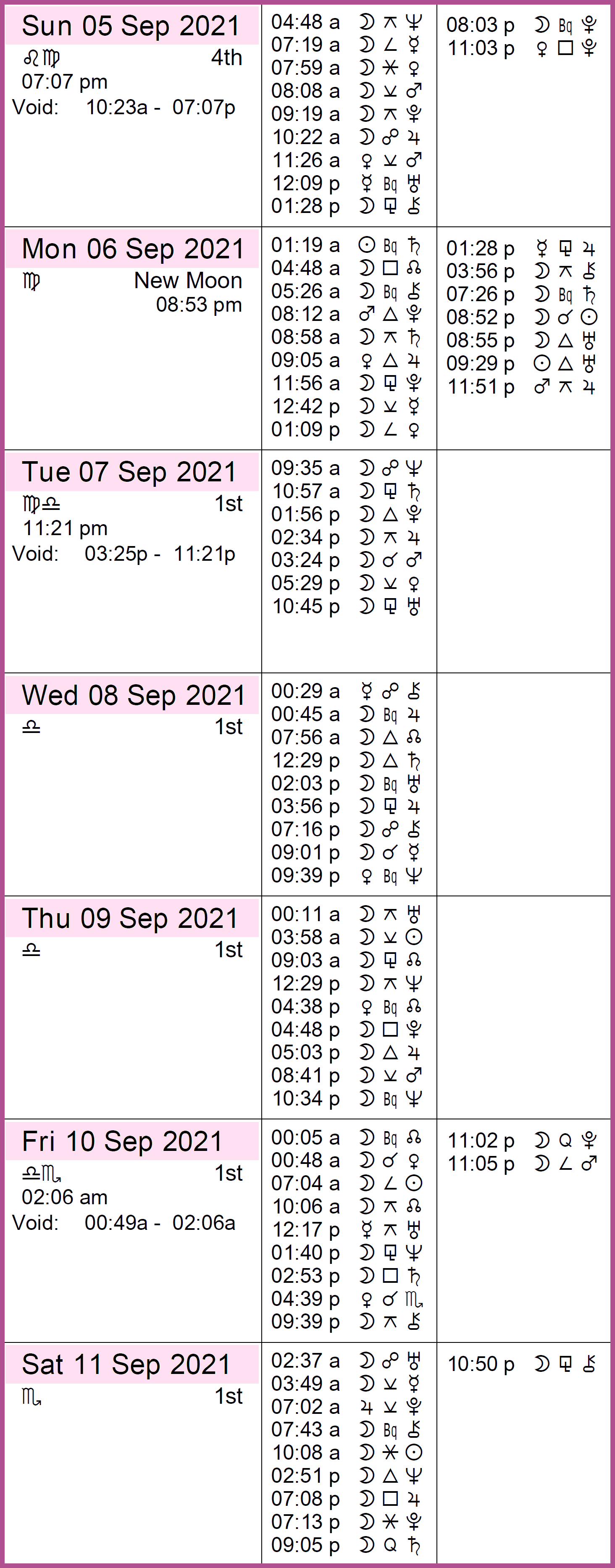

| September 8, 2021 | We |

| September 9, 2021 | Th |

Re:

| September 8th, 2021 | |

| The Sun is in Virgo | |

| The Moon is in Libra The New Moon is in Libra: All day | |

| Next Mercury Retrograde Period Sep 26 - Oct 18 | |

| Mercredi 8 Septembre 2021 15h13 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paris

Wed, Sep 8, 2021

MERCREDI08SEPTEMBRESemaine 36 - Jour 251 | NativitéP Premier croissant

Fête du 8 Septembre : Nativité

Aujourd'hui, nous fêtons également les Saint Adrien, Sainte Adrienne, Saint Ammon, Sainte Belline, Saint Corbinien, Saint Eusèbe, Saint Néotère, Saint Nestabe, Saint Nestor, martyr, Sainte Pélagie, pénitente, Saint Victor.

|

Sun enters the next Sabian symbol at 10:36 h (chart) |

| Sunrise 07:15 |

| Sunset 20:19 |

| Twilight ends 22:11 begins 05:23 |

2%

1 day old

2nd Lunar Day

This Lunar Day is propitious to ambitious and lucrative ventures, commerce, but also dreams, far-fetched ideas or plans.

Waxing Moon

A good time for long-term partnership and for starting the implementation of far-reaching plans.

Moon in Libra

Suitable energy for sharing, decorating, being artistic, holding meeting, conflict resolution, diplomatic missions, weddings, engagements, parties, gifts, fantasy reading, falling in love, hairdressing, making oneself beautiful. Purchase of articles of clothing, cosmetics, furnishings, flowers, jewellery, art equipment.

| Rise | Set | |

| Mercury | 09:47 | 20:56 |

| Venus | 11:06 | 21:31 |

| Moon | 08:37 | 21:21 |

| Mars | 08:11 | 20:41 |

| Jupiter | 19:35 | 05:25 |

| Saturn | 18:51 | 03:51 |

| Planet | Aspect | Planet | Orb |

| Sun | Trine | Uranus | 1.47 |

| Moon | Trine | Saturn | 1.93 |

| Moon | Trine | Lilith | 0.02 |

| Moon | Trine | True Node | 0.77 |

| Mercury | Quincunx | Uranus | 2.46 |

| Mercury | Opposition | Chiron | 0.44 |

| Venus | Trine | Jupiter | 2.55 |

| Venus | Square | Pluto | 2.83 |

| Mars | Quincunx | Jupiter | 1.05 |

| Mars | Trine | Pluto | 1.34 |

| Jupiter | Trine | Venus | 2.55 |

| Jupiter | Quincunx | Mars | 1.05 |

| Saturn | Trine | Moon | 1.93 |

| Saturn | Trine | Lilith | 1.94 |

| Saturn | Trine | True Node | 2.69 |

| Uranus | Trine | Sun | 1.47 |

| Uranus | Quincunx | Mercury | 2.46 |

| Neptune | Sextile | Pluto | 2.55 |

| Pluto | Square | Venus | 2.83 |

| Pluto | Trine | Mars | 1.34 |

| Pluto | Sextile | Neptune | 2.55 |

| Chiron | Opposition | Mercury | 0.44 |

| Lilith | Trine | Moon | 0.02 |

| Lilith | Trine | Saturn | 1.94 |

| Lilith | Conjunction | True Node | 0.75 |

| True Node | Trine | Moon | 0.77 |

| True Node | Trine | Saturn | 2.69 |

| True Node | Conjunction | Lilith | 0.75 |

19° / 35°

19° / 35°Risque de pluie : 81% - Humi. : 62%

Vent :Est - 24 km/h

Lever : 07:17 - Coucher : 20:17

Averse de pluie modérée ou forte

| Planet | Starts | Ends | Planet | Starts | Ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07:19 | 08:24 |  | 20:18 | 21:13 |

| 08:24 | 09:29 |  | 21:13 | 22:09 |

| 09:29 | 10:34 |  | 22:09 | 23:04 |

| 10:34 | 11:39 |  | 23:04 | 23:59 |

| 11:39 | 12:44 |  | 23:59 | 00:54 |

| 12:44 | 13:49 |  | 00:54 | 01:49 |

| 13:49 | 14:54 |  | 01:49 | 02:44 |

| 14:54 | 15:58 |  | 02:44 | 03:40 |

| 15:58 | 17:03 |  | 03:40 | 04:35 |

| 17:03 | 18:08 |  | 04:35 | 05:30 |

| 18:08 | 19:13 |  | 05:30 | 06:25 |

| 19:13 | 20:18 |  | 06:25 | 07:20 |

No milk or water: Shoppers face shortages at UK grocery stores

Sep 08 2021

Empty shelves in a Sainsbury's supermarket in London

London (AFP) - The supply chain troubles caused by Brexit and the pandemic have been so bad for Satyan Patel that the shelves at his convenience store in central London are seriously lacking water and soft drinks.

“Last week I ran out of Coca-Cola. I haven’t had large bottles of Evian for three weeks,” said Patel.

“Without products, there’s no business. With empty shelves like this, no one is going to come in the shop anyway,” he added.

A wide range of businesses have suffered through shortages for several months in the UK – from milkshakes at McDonald’s to beer at a pub chain to mattresses at Ikea.

But shoppers are also facing empty shelves for things as basic as water and milk at UK supermarkets and grocery stores.

The coronavirus crisis has severely disrupted the global supply chain, but Britain’s divorce from the European Union late last year has exacerbated the problem in the UK.

Shops are not getting products delivered to them as rules making it harder to hire EU citizens has left haulage companies with a drastic shortage of lorry drivers.

Many people who returned to their home countries from Britain during the lockdown have not returned.

Co-op, a cooperative supermarket group, said it was “impacted by some patchy distribution” to its deliveries but it was working with suppliers to re-stock quickly.

The group said it was recruiting 3,000 temporary workers “to keep depots working to capacity and stores stocked as quickly as possible”.

- Where’s the milk? -

According to recent estimates, the UK currently faces a shortage of about 100,000 lorry drivers.

“We had already decided to reduce our stock because of Covid… but now we’re finding it hard to get some products as well because they’re just not available,” Patel said.

One shop assistant said some customers blamed them for the shortages

At a supermarket near his store, the soft drinks aisle was a little short of bottles and cans but other shelves were full.

But 22-year-old sales assistant Toma said the situation was grim.

“We don’t have stock, we have nothing in our warehouse,” said Toma, who declined to give her last name.

“We have gaps everywhere,” she said. “Sometimes we receive only a certain amount (of some products). We don’t even have water.”

The shortages began when the pandemic hit and got worse after Brexit came into force on January 1, Toma said.

Some customers complain to supermarket staff and “say it’s us to blame”, she added.

At another major supermarket in southeast London, water bottles were sparse and milk was missing from shelves.

Frozen-food group Iceland and retail giant Tesco have warned of Christmas shortages.

Iceland head Richard Walker said the company has reduced deliveries as it has 100 fewer drivers than it needs.

“Every day we are missing around 10 percent of the stock we have ordered into our depots,” he wrote in a blog, adding that “when things were at their worst” its sole bread supplier was unable to deliver to as many as 130 stores per day.

- ‘Perfect storm’ -

Shortages of goods in the UK “will probably last for a while and may even intensify further”, according to a note by Capital Economics, a research consultancy.

A report this week from the Confederation of British Industry cited the Road Haulage Association as saying it would take at least 18 months to train enough Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) drivers to replace those who have left.

Signs apologising for the lack of stock are now a common sight in British shops

For the CBI, the dual effects of Brexit and Covid-19 are a “perfect storm”.

Stock levels in relation to expected sales fell by more than 20 percent to a record low across the retail and distribution sector in August, according to the CBI.

The group has urged the government to be more flexible on immigration and add skilled lorry drivers to a list of professions that are short on workers.

Road transport companies and businesses dependent on deliveries are offering bonuses and higher wages in an attempt to retain drivers, but the moves have raised concern that they could contribute to rising inflation.

Ryan Koningen, a 49-year-old project manager at a company in the City of London, said his colleagues often discussed the situation and “the question of costs: will they rise because drivers are paid premiums?”

He too said he had noticed shortages of “day-to-day products”.

Agence France-Presse

AFP journalists cover wars, conflicts, politics, science, health, the environment, technology, fashion, entertainment, the offbeat, sports and a whole lot more in text, photographs, video, graphics and online.

© 2021 AFP